What is a gazetteer?

In traditional terms, a ‘gazetteer’ is a geographical index or dictionary. In the digital world, online gazetteers like Pleiades or the World Historical Gazetteer play a crucial role in the Linked Data ecosystem since they disambiguate and geo-locate places, and define stable identifiers (URIs) that facilitate the open reuse of such data.

Apart from a few pioneering projects, digital gazetteers (like Pleiades and WHG) have conventionally been concerned with the disambiguation of places at the macro, site level. With regard to antiquity, Pleiades has, for instance, provided disambiguation, geo-spatial location, and URIs that differentiate between the city of Alexandria founded at the junction of the Indus and the Acesines rivers, and the other, better-known Alexandria in Egypt’s Nile Delta, as well as other places of the same name. Reuse of Pleiades ID numbers and URIs within an LOD environment enables a user to label their data in a way that makes clear to both computer and human users that the data point in question pertains to the Egyptian Alexandria rather than the place today in Pakistan (or any other ‘Alexandria’) that was once known by the same name.

Digital Urban Gazetteers

Many of the same problems that have led to the creation of digital gazetteers on the macro scale are also a challenge at a finer, site-specific level of granularity. How do we make certain that a computer and a human researcher can ascertain that an object in question came from this “Temple of Jupiter” (in modern Split, Croatia) not that “Temple of Jupiter” (in modern Athens, Greece) since traditional keyword searching would inevitably produce results that confuse the two geographically distinct places? How can we be sure that a researcher will turn up all the relevant results when searching for information pertaining to the building known as House F in block D5 at Dura-Europos, when over the course of the last hundred years since its excavation different authors have referred to that same building by different names, including ‘House of the Great Atrium’, or ‘House of the Cistern’. Once again, in order to be comprehensive, traditional keyword searches would require quite a bit of previous knowledge on the part of the researcher.

Therefore, what Pleiades and WHG have historically done on a macro-level with regard to disambiguating and geo-locating cities, and compiling all name variants for individual places, is akin to what a digital urban gazetteer does on the micro, site-specific level. Digital urban gazetteers provide unique identifiers, in the form of URIs, that help to disambiguate potentially confusing naming traditions associated with individual buildings or other features within a city or site and associate those places with specific geo-spatial coordinates.

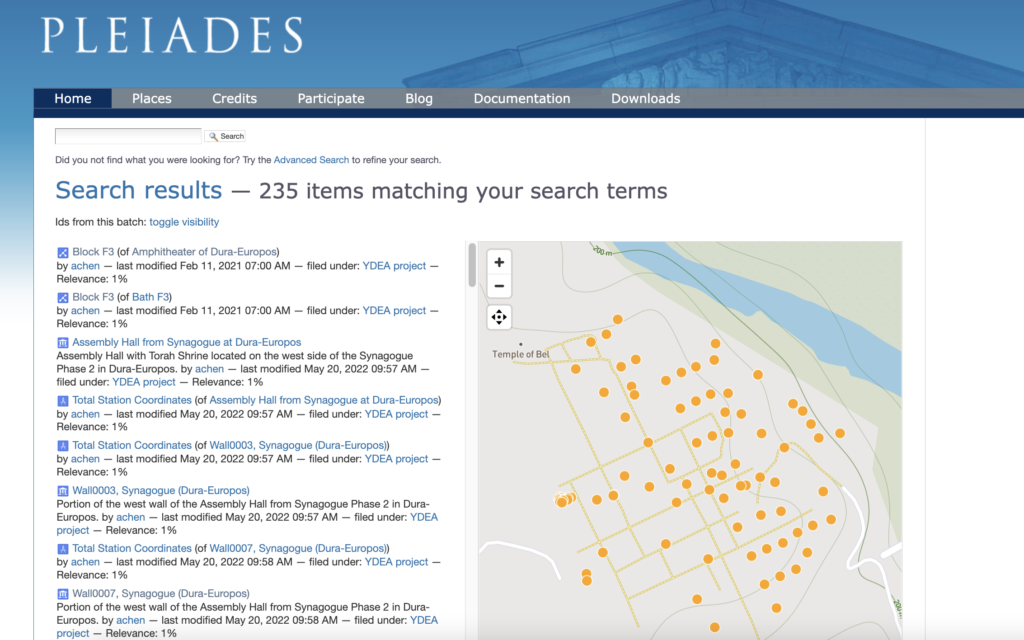

IDEA is pleased to be working in partnership with Pleiades to systematically develop an urban gazetteer for the site of Dura-Europos. Among the many benefits of a gazetteer with site-specific granularity are its uses to:

- Disambiguate different places with the same name, but different geographical locations.

- Make clear when a single place has multiple names it has been associated with over time (or among different groups).

- Disambiguate instances where there is a feature at the same place, with the same names, but chronologically different archaeological levels.

For IDEA’s purposes, the Durene urban gazetteer is conceptualized as a critical tool to enable the virtual reassembly of artifacts and other archaeological data points kept and catalogued by distinct collections, in multiple languages, and in various parts of the world. But apart from this project-specific functionality, IDEA’s work in this regard is significant because it is one of the first projects to attempt the systematic codification of an ancient archaeological site for the purposes of creating an urban gazetteer that can in turn serve as a tool for the digital reassembly of dispersed data within an LOD environment. It is our hope that the documentation and dissemination of our process and lessons learned may therefore be of use to other projects aimed at similar goals, no matter their chronological or geographic particulars.

We are exploring how to put this feature intentionally to use as part of a strategy for preserving intangible heritage and improve the searchability of cultural heritage information according to local names and traditions.

Browse Dura’s gazetteer entries in Pleiades: